Looking for the audio version of this story? Scroll all the way to the bottom!

The following is the account of Jane Erengua, wilderness courier for the city-state of Atlanta.

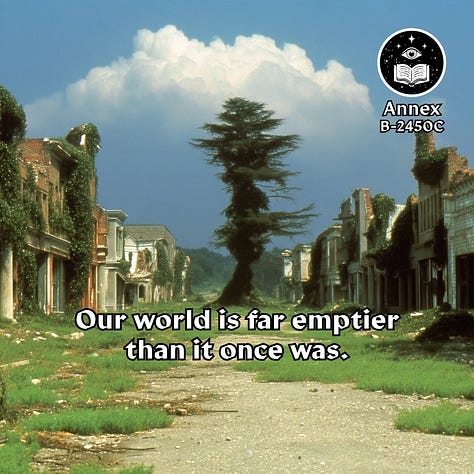

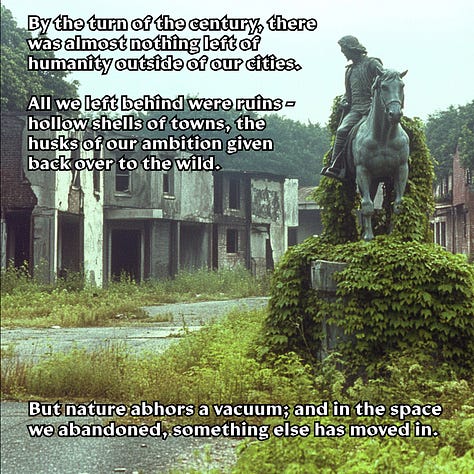

The sun is sinking low when I at last spy the remnants of the old town. Its rotting buildings rise out of the mist, sagging mounds of wayward green, like giant tombstones long ago consumed by moss. This place is in far worse condition than it was when I last passed through. The kudzu has swallowed all parts of the town save the head of the statue that stands in the old square. The man the statue depicts, some civil war general I think, looks less like a leader of men and more like a man drowning these days.

I’m not happy to be here. I’d hoped to be through this portion of the country by the time night fell, striding across the open plains and free of the oppressive clutches of the forest. I would have been, if not for the mask-wearer that’s taken up residence beneath the bridge over the river. It had found the bridge abandoned, and so it was HIS it said, and to pass I would need to pay a toll. I turned heel at that and set off searching for the old rowboat hidden further down the bank. No bargain is ever worth making with these beings, even if it means the difference between sleeping somewhere safe or somewhere fraught with danger.

I’m not exactly sure which of those this old town is. The old courier that used to run my route told me never to spend the night here if I could help it, and thus I never have. He also told me that when the sun falls, it’s always safer to make camp than it is to keep moving through the dark. He was a man of persistent never’s and always’s, even when his absolutes contradicted themselves. I’m not sure what he’d do in this precise situation, but I do know what happened the last time I tried to travel through the night. The scar below my belly button, my souvenir from that foolish traipse, aches like it always does as I race to set up my tent, a lasting reminder of my moonlit mistakes. I’ve just finished laying out the circle of salt around my tent at the base of the swallowed statue when the sun’s final rays vanish behind the trees, and I finish eating my dehydrated dinner as the first stars begin to shine.

It’s cold here, colder than I expected for this time of year. I silently curse myself for not bringing a thicker jacket and entertain the idea of a fire for a few seconds before casting the notion aside. No fires. No light. Never attract unnecessary attention, especially when you’re in unfamiliar territory. If there’s one thing that’s sure to catch unwanted eyes out here, it’s manmade light. The damn things that go bump in the night are like moths in that way. Creatures of the dark, always drawn intractably to the glow of something new and strange. I’ve made that mistake before too, and I can tell you with certainty that I’d much rather hunker down in the pitch black, blissfully blind, than be able to see the things floating in the night, gazing at me, just outside my circle of salt. It’s an unnerving thing to be watched so intently, so HUNGRILY, by things only just barely out of reach. My grandmother tells me that back in the day, when the stores were many and the shelves were always full, that there used to be a tank of lobsters that you could pick from to take one home and cook. I can’t say for certain, but I feel like those poor aquatic bugs of the past may have known better than any human what it feels like to be watched in such a way.

I sit in my tent, contemplating lobsters with my legs in my sleeping bag, brushing my teeth as swiftly and silently as I can. It’s deathly quiet here, both a blessing and a curse. From within my tent, I can hear things moving through the thick underbrush around me. Most of the sounds are ones that I recognize – the careful trot of a deer, the frantic rustling of a mouse, the slow plod of a possum. It’s the noises I don’t know that cause my heart to race and my ears to ring. A sliding, dragging sound, like something wet and heavy pulled across fallen leaves. A soft laugh that becomes a sob. A clacking rattle, like a bag of bones swung in circles overhead. I dare not look out. If I do not see the sources of the sounds, they will have less power over me. None can come within my circle of salt anyway, and eventually I fall into fitful sleep – until I am woken first by the howling of wind, then roused more suddenly by the whisper of words. A song, sung hushed and slow – from right outside my tent.