The Ranger

The following is the account of Robert Rounk, backcountry range with the North American Union Bureau of Wilderness. Selected from Annex C-7322M.

Already read this part of the story? Scroll down for the continuation!

Looking for the audio version of the continuation of the story? Scroll to the very bottom!

The following is the continued account of Robert Rounk.

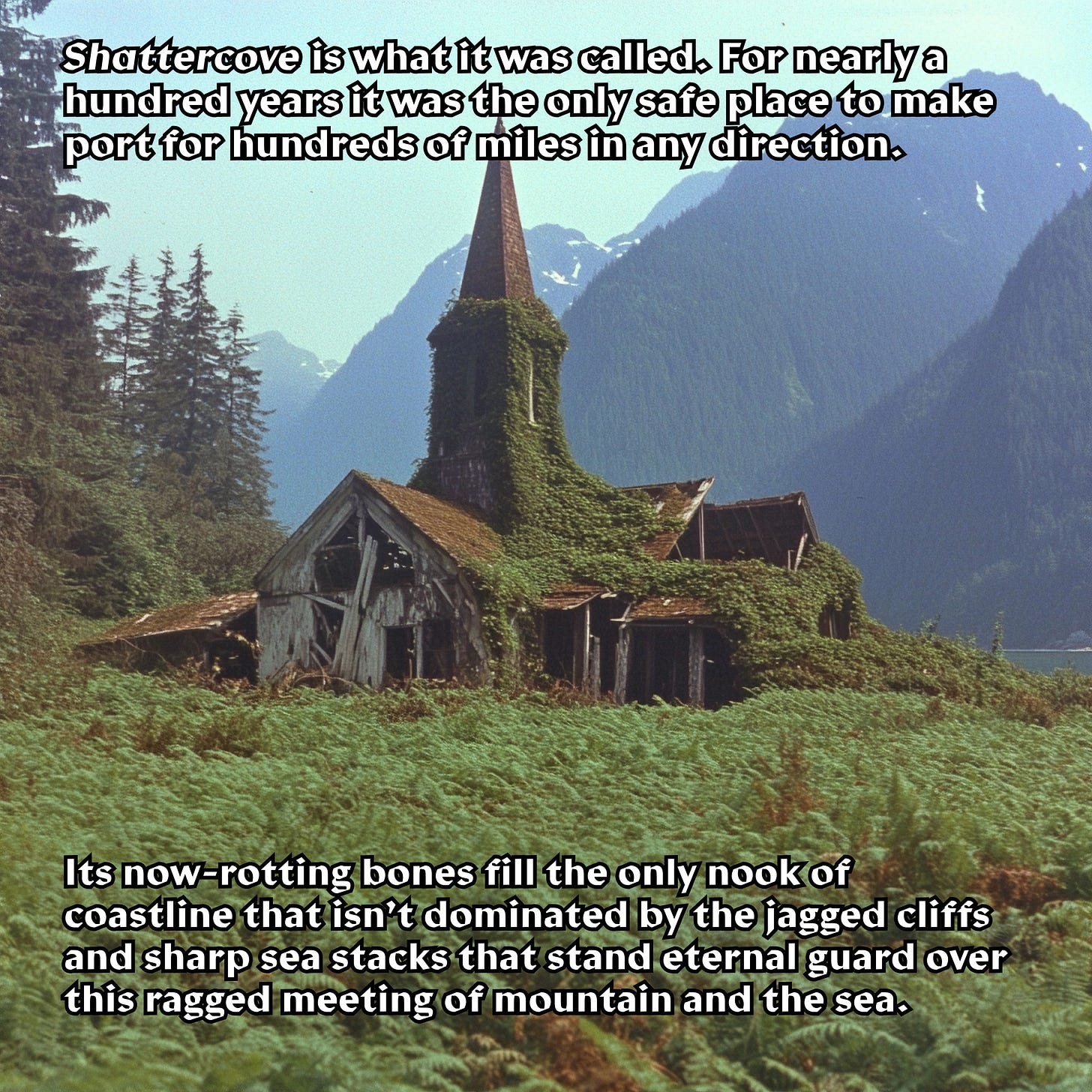

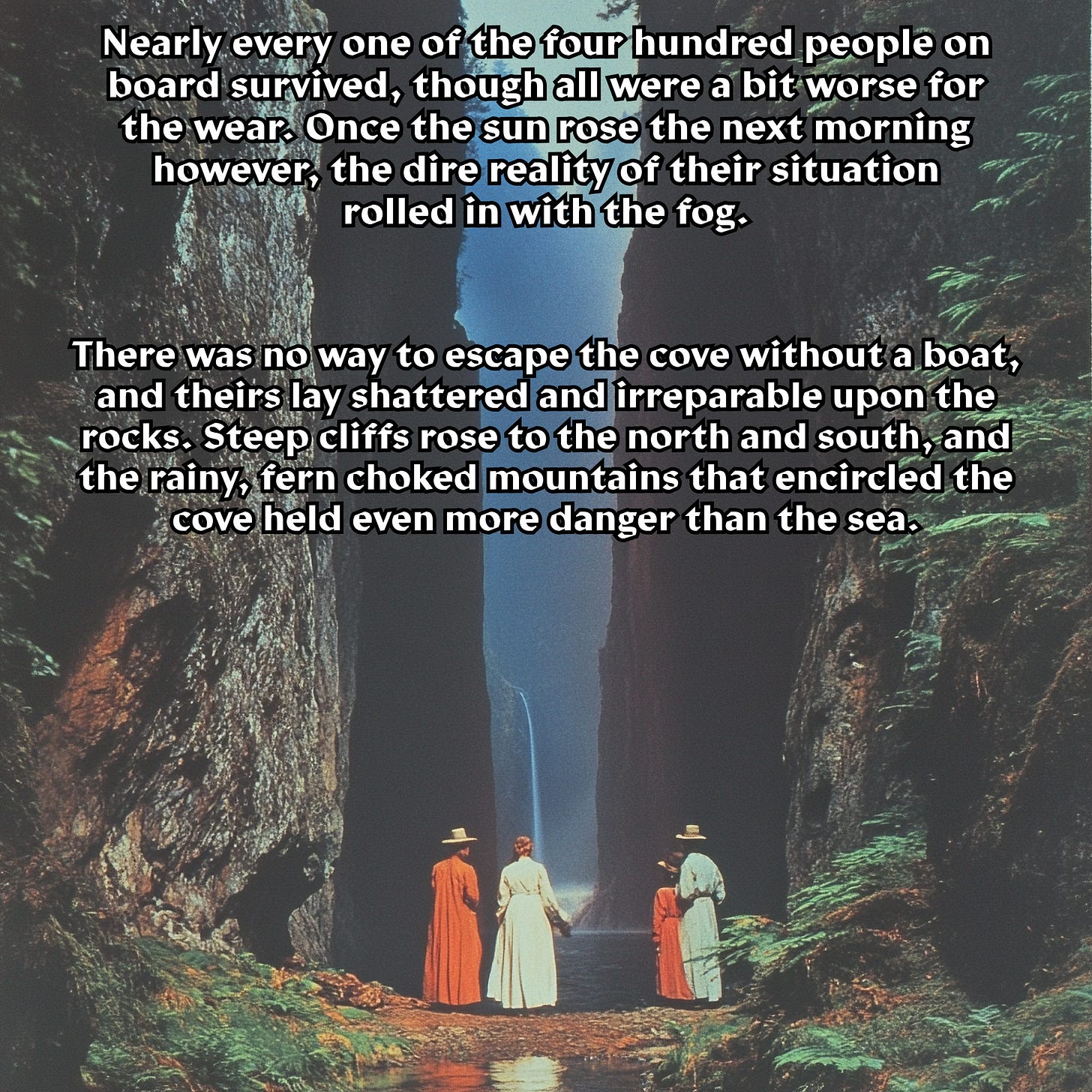

There is a chill in the air. Not one so sharp as to turn me around, but certainly enough to give me pause as I approach the rotten, fern-choked fence line that marks the edge of Shattercove. A small sign lays in the dirt, so faded that its barely legible message of “NO TRESPASSING – PROPERTY OF THE STATE” is spelled out in dusty outlines rather than the bold, painted letters that once filled their space. It is a weak sign, far from fearsome enough to dissuade me after my hike through the mossy gullies and across the windy ridgelines I traversed to get here. It speaks to how well and truly this place has been forgotten, even by the government bureau that manages the land it rests upon. Only my old maps from the 80’s mark the town; upon all the newer ones it has vanished entirely. I look up past the sign as a light breeze blows from my seaward side, bringing with it fingers of fog that snake their way between the collapsing buildings and down the narrow streets, kissing the moss and caressing the vines that are slowly pulling what remains of this place into the earth below. I step over the fence line, and into the town. Somewhere in the forest, a coyote begins to howl.

This is my first time entering Shattercove. I first laid eyes on it four years ago, while patrolling the trails to the north of my cabin. Much like tonight, my eyes had been drawn to the diminutive ruins not by chance, but by a light. A flickering yellow glow, like a candle on the horizon. I had approached it then, thinking the ruins occupied by a squatter or dope farmer, but upon reaching the trail that led down to the ruined settlement saw no lights and heard no sounds other than the rumble of swiftly approaching thunder on the horizon. Such a looming atmospheric threat that was more than enough to send me running back to my cabin before the rain began to fall; hard and fast for the next two weeks without end.

I phoned my supervisor Al the next morning to ask if I should go back out and investigate. “Only if you want to die in the storm.” Had been his curt response, a strangely cold sentence from such a generally jovial fellow. I forgot about the town entirely for the next few months, until I saw the same lights again. With no storm on the horizon, I thought it a good time to go back and take a deeper look, but called to clear it with Al beforehand as the old bureau maps marked the place as strictly off limits.

“Don’t worry about that damn town. There’s no one there, and even if there were they wouldn’t be your concern.”

I’d pushed back on that, asserting that if there was someone in Shattercove we should find out what in sam hell they’re doing down there. Might be that they’re in need of assistance, or possibly on the run from the law or otherwise – I couldn’t imagine much else that would bring someone all the way out here. He very nearly yelled in response.

“Goddammit Robbie, if I’m tellin’ ya to stay away from that ruin of a town, then you just shut up and listen. You’re out there to keep tabs on the woods, not Shattercove. It ain’t gonna exist in a decade or two, and neither will any fool who’s decided to hole up there. I don’t care what you see, hear, or SMELL comin’ from that place, you just stick to keeping track of the trees and the animals, NOT whatever ghosts you think you’re seeing down there. I don’t want to hear another word about that place, ya hear?”

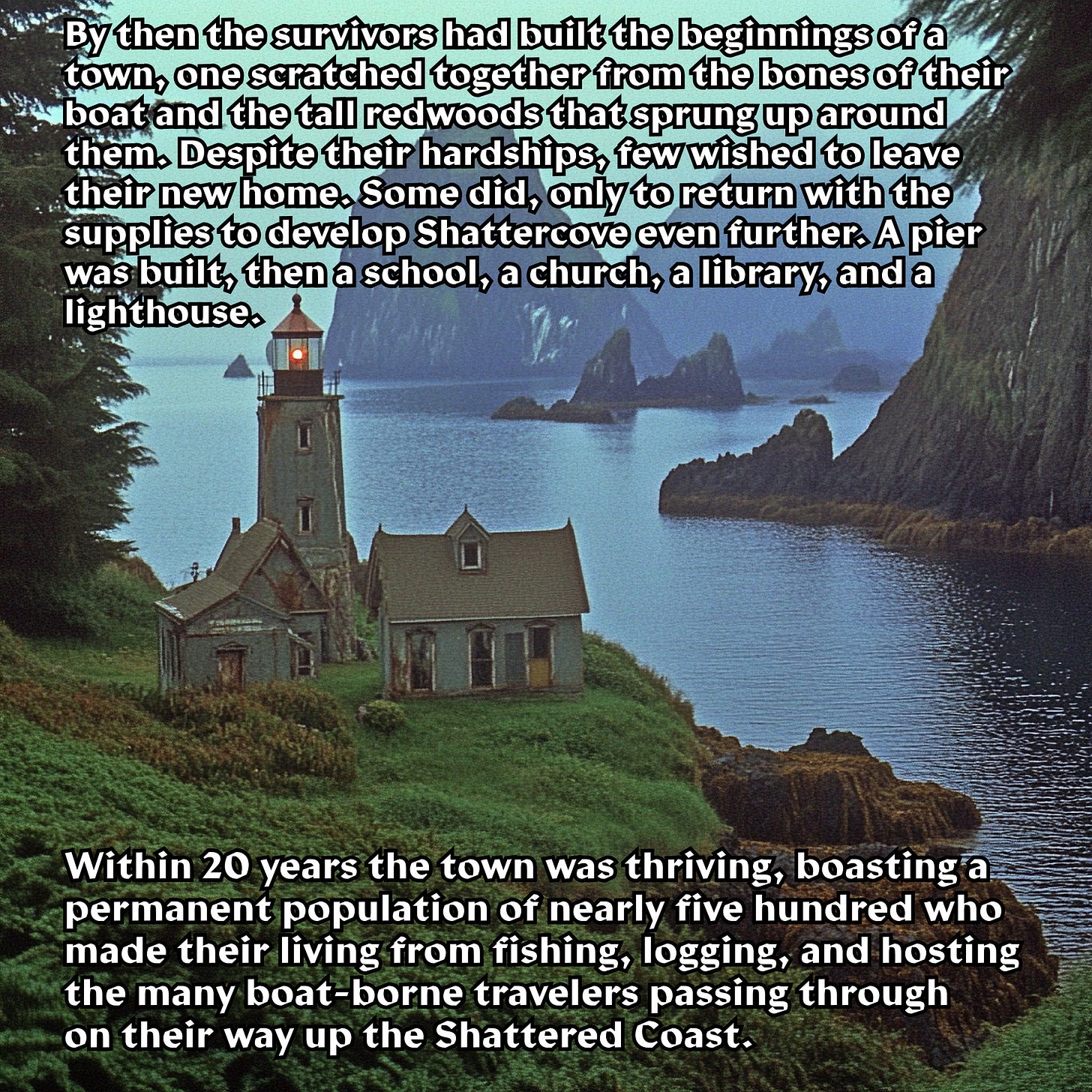

He'd hung up on me then. There’s little more troubling than loud anger spilling from the mouth of a gentle man, so I, rattled as I was, let it drop. His tirade did little to douse my curiosity however, and though I stopped trying to investigate the old town, my curiosity only grew with every strange occurrence that it threw my way. The flickering lights seen just before dusk in the windows of the old town hall were the most common, but I’ve also heard the old foghorn sound (despite the lighthouse being out of commission for more than 40 years), seen smoke rising from the chimneys, listened to what sounded like the songs of a symphony float up from the cove, and witnessed mornings where a stubborn dome of dense fog clings to the town, long after the skies have gone clear and blue. I swore that before I left my post, I’d come take a closer look, Al’s rebukes be damned, and now that they’ve told me my position as backcountry ranger is being cut, that time is now. The flickering yellow glow I saw through my binoculars just an hour ago was the last sign I needed to pack my patrol bag, lace my boots, and make the trek down to the old town.

Mud squelches beneath my feet as I walk between the buildings. The ferns that once filled the creek side gully the town inhabits have retaken their lost territory and the rotting wooden buildings rise like tombstones, poking up between the thick mass of green. I stop at a small crossroads to orient myself – the light I saw from the ridge was coming from within the old town hall, and that’s where I want to go. It’s at the back of the town, closest to the edge of the woods, so I turn right, and stride away from the ocean. The waves crash behind me, and I can smell the tide receding with the daylight as I pass rows of collapsing buildings on either side.

Rounding a bend, I come across Shattercove’s small church, a building in even worse condition than the rest of the town. The once-holy house seems half sunken into the earth, and the only thing left to distinguish it as a place of worship is the moss-eaten shape of a cross hanging lopsided above the door. Peering inside, I see pews occupied by a congregation of tall ferns and a redwood sapling growing through the roof where the priest and his pulpit once stood. I turn to leave, accidentally kicking over a small rock in the doorway as I do. I glance at it in passing, look away, then look again. Carved into the side of the rock that had been buried in the dirt is a roughly hewn symbol. Two interwoven circles, like a venn diagram, with a single line passing through them both. Curious. I reach to pick it up, when suddenly I hear it – a song, played on a fiddle, drifting through the now-thick fog from the edge of the town, in the direction I had been walking. I jolt upright, abandoning the rock to its place and the church to its fate as I walk briskly toward the music.

The fog grows thicker by the second, and my headlamp cuts a yellow beam through the blueish gray murk as I approach the town hall. The old building still stands somewhat tall, even in its disrepair, by far the tallest building in town other than the old lighthouse. The shadow of its steeply pitched roof sprouts from the mist, a crooked and hunched silhouette standing on the very edge of the towering forest that seems ready to swallow it from behind. The music still floats softly through the air, but with every step I take toward the hall, it fades, until it ceases entirely as I ascend the stairs to the door. Above the entryway a woman carved out of wood stands tall, her hand reaching out toward the sea. A rusted metal plate bearing the word “Penance” – the name of the boat that carried the first settlers to this cove - hangs by a single nail just below her. She must have been cut from the bow of the ship. Whatever beauty she held in those old seaward days has long fled from her now. Half her face is covered in moss, and the rest of her crumbles beneath an everlasting onslaught of ocean air and voracious termites. I tip my cap to her as I pass through the doorway and enter the old town hall.

Inside, a strange scene greets me. The building is… hollow. From outside it seemed complete (at least as complete as one could call a building in such disrepair) but within, the floors, benches, walls, and rooms you may expect to find are gone entirely, as is the back wall. It is as if someone built the frame of a town hall over a growth of ferns, and never bothered to fill it in. A creek departs the thick wood in the rear of the building and runs directly through the middle of what would be the floor before disappearing into a small hole in the ground just before reaching the front door. Built along and over its path are archways of thatched twigs and woven vines, strange handiworks of a kind I’ve not seen before. I approach the archway nearest to me, and find a freshly picked flower woven into it, no more than a few hours old. A chill runs down my back, and fear rises like a rogue wave within me. I am about to turn around, to run, when I look up and see it through the archways – a flickering yellow light, floating in the trees where the creek begins to disappear into the dense forest beyond.